Sequence of Memories

2017-2021, materialized blockchain of visual information, developped with Pinterest search engine (see text below), mixed media 40 x 25 x 600 cm (configurations variable, depending on space), courtesy Lang Art, exhibited at Art Rotterdam 2021. Made possible with kind support from Beeld and Mondriaan Fund.

Sequence of Memories is the physical manifestation of a visual dialogue between the artist and Pinterest. For this work, originally developed as a contribution to the artistic documentary Parallel by Ruth Meijer and Ellen Blom, Bolink first made a small sculpture of the letter π and pinned a photo of this sculpture to a Pinterst board. For every image pinned, Pinterest’s search engine suggests 300 smilar or connected images. Bolink chose one of them, a historic sewing machine wrapped in a crocheted cloth, and made sculpture no. 2 from the series based on this image. This was followed by an Indian pancake (appam), a bat embryo, a Turkish plug, a bar of soap and a number of other objects. The stated goal was to make a series of 15 objects in total, in which the fifteenth object would occupy a special place, as an apotheosis. To his great surprise, Pinterest delivered in the very last set an image of a cardboard card with a question: “can computers ever become conscious?” Has Bolink become blinded by his own preconceived expectations, is it just a coincidence, or are the algorithms of Pinterest playing an intelligent game with us and are their actions comparable to what we call thinking?

7 x 7

Ceramics, spraypaint, 2018, 28 x 25 x 160 cm courtesy Lang Art

A monument dedicated to number 7, based on the premise that all figures except 0 and 1 will be superfluous in a 100% binary future. Monuments for the other seven left over figures (2,3,4,5,6,8 & 9) will possibly be produced later. Blockchain of visual information developed with Pinterest and the artist, see text above. For more information watch this short film by Marc van Dijk.

Grand Piiiiiano Oracle, 2019

Wood, synthtetic leather, digital piano, robotic hands, soundsystem computers and other hardware, 90 x 150 x 220 cm, courtesy LangArt

This interactive grand piano sculpture has been developed for a show at Club Solo in Breda and has later been exhibited at LangArt Amsterdam. It responds to questions posed to the Google assistant via a built-in microphone. The answer to the question will sometimes be silence, but in many cases translated into music and the activation of the robotic hands playing it. In the original version the piano was played by hands connected to a large arm outside the instrument, later this has been replaced by hands operating from inside the instrument. Below an eleborate text by curator and author William Myers:

As the Prophet Profits

By William Myers

May, 2019

In a high-ceilinged studio in Amsterdam, the sculptor Merijn Bolink constructs the frame of a grand piano combined with plastic, disembodied arms and hands to press its keys. Hidden in the classic mechanical instrument is a digital wonder, a heart of silicon pumping data into and out of its center, streaming its wisdom into the piano that sings a most uncanny tune in response to a simple question “Who was Miles Davis?.” This installation is called Grand Piiiiiano Oracle, and its functioning, references, and deeper implications stretch from ancient Greece to our present state of technological fetishization, to our uncertain future and collective grip on the truth.

Oracles have existed for millennia and across cultures, embodied in a person thought have a link to divinity. Through them the gods could speak to people directly, predicting the future, proffering warnings, or bestowing some otherwise unobtainable knowledge. These oracles were passageways or bridges to an indescribable wisdom, and were carefully guarded or controlled resources. Once only referring to a person, such as the Pythia, the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, the world “oracle” eventually expanded to describe things or places, such as a monument or temple that could be visited to receive premonitions and messages.

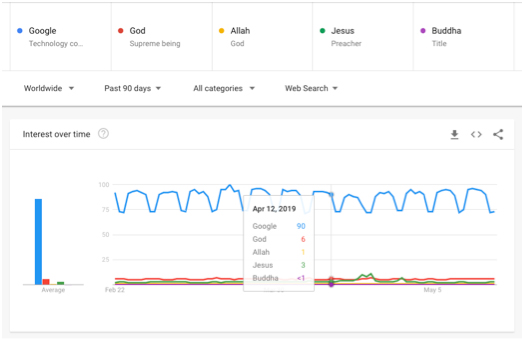

Today we have a new, more democratic or, at least, more widely distributed oracle, one that is almost like a god: virtually omnipresent, all-knowing, and likely immortal. It is asked approximately five billion questions every day in dozens of languages, and provides answers faster than an eye can blink. In fact, a recent update to the algorithms that power its capacity to understand a question and retrieve relevant knowledge and make predictions was named Hummingbird on account of its speed. Of course, this contemporary oracle is the Google search engine. Accordingly, the company’s own research tools show that Google’s popularity as a topic already exceeds that any of the world’s religions or even divine figures such as Jesus, Allah, or Buddha.

The Google Assistant is a product connected to the search feature, delivering on the promise of the disembodied “computer” in science fiction settings, such as Star Trek, where an ambient digital assistant stands ready with answers to any question imaginable. This represents a leap worth considering, as it creates a kind of live dialogue between a person and a machine, within which sits a deep well of knowledge and a type of wisdom that is always growing and changing, getting simultaneously more and less humanlike. That is, even as it builds aptitude in mimicking human behavior, copying familiar ticks of speech for instance, it is also becoming so much more powerful, far surpassing human consciousness in all its complexity and creativity.

Grand Piiiiiano Oracle by Merijn Bolink can be both frightful and funny, combining and compressing the reality of our modern oracle and translating its pronouncements into music. The content is visitor-generated, as Oracle must be asked a question. The answers that are spoken by the Google Assistant within the piano are analyzed by software that maps qualities of their sound, such as the rising and falling of the voice. The many attributes of the spoken answer are then transformed into musical notes, strung together and played. The subsequent performance of the Google-derived musical mini-scores is made by digital and analog means, via custom-crafted instruments along with off-the-shelve sound technology housed in the piano.

The musical answers to visitors’ questions vary in length, but are often based on the Google “snippet,” or the string of words comprising a short paragraph that the algorithms conclude is the most likely answer to your question, based on related content originating what it deems to be high quality websites. Of course, like all technology of this kind, it can be wrong. Sometimes hilariously or alarmingly so, as with the query “why are fire trucks red?” which for a time delivered content from a Monty Python joke, or “what happened to the dinosaurs?” prompting an answer from a creationist website calling the science of Paleontology a conspiracy. Questions about Barack Obama, whether women are good or evil, or which US Presidents belonged to the Ku Klux Klan (actually, none) often return shocking results. Such errors reflect the larger and worrying trend in which algorithmically sorted, ranked, and even generated content that is misleading or false can spread globally in an instant. This is not only destabilizing to our sense of truth but can and is harnessed to hurt or kill people by inflaming passions, as was the case in India with wrong information about child abuse being forwarded over WhatsApp.

In effect, Grand Piiiiiano Oracle, by taking Google’s supposed wisdom and giving it musical expression, is also making it unreadable. This highlights the reality of what we all do when we interact with Google, which is to decode layers of content, barriers to understanding, that inevitably stand between our questions and the actual answers. Our reading of the response, as it were, requires not just a basic understanding of how Google works, and access to the screen or speaker, the internet, and a source of electricity. It demands filtering, knowledge about what sort of things Google can be trusted to give a reliable answer. Converting square meters to square feet is one thing, it is quite another to ask about the existence of God, the definition of freedom, or the public health merits of vaccinations (they are plentiful). One must reverse engineer their question from a place of knowledge of what categories of questions Google struggles to answer well, on account of what is contentious in society or what topics or prone to generate misinformation.

Since the time of ancient oracles, we pieced together truths from a variety of sources: family, friends, colleagues, institutions, figures of authority, books, and our own experiences, mainly. This was imperfect of course, and contingent on the vagaries of power, free speech, and our access to media. But the variety of sources lent a special quality, the wide distribution of the power to dictate what is true. This dispersal, across so many people, organizations and interests, is collapsing into one place and one firm: Mountain View, California, in the offices and data centers of Google. Setting aside for a moment the question of whether this is a good idea, are most people even aware of this profound shift?

The network effect is a glorious thing in the world of technology, the notion that the more users of a platform, the more valuable and useful it becomes. Growth, in this model, initiates a virtuous cycle of more growth and even more momentum. But what is true of a technology platform that is essentially a product to sell advertising is in conflict with how civilization has worked to entrust the pursuit of truth to a distributed network of specialists and organizations. Take the study of Philosophy for example: there are today thousands of professors around the world teaching the subject in different ways and from varying perspectives, cultivating a richness in thought, a complex diversity of ideas. It is only from such a resilient ecosystem of minds that anything resembling truth might arise and endure. The Google-like model of education would be comparatively brittle: a single trusted and highly-ranked lecturer, probably from a place like Oxford University, would record and upload their instructions and a textbook, and that would become the dominant version of philosophical inquiry.

The oracle that is Google tries to deliver to us what we reflexively want but is bad for us: the one true instantaneous answer. We trade our attention and data for it, and Google, the Prophet of Mountainview, profits tremendously.

The observance of all this troubling reality feels present in Grand Piiiiiano Oracle, the form of which is vaguely reminiscent of a creature, with a scaled skin and claw feet clasping orbs. Bolink seems to have almost equal doubts and hopes about a future characterized by artificial intelligent systems like the Google Assistant. At this stage, he sees it as like “a child that’s just learning to speak. It creates these funny sentences, but sometimes they contain the truth.” Some of the formal qualities, such as the black leather-like material on the arms, suggest fetishization, something we as a society do with technology, expecting it to satisfy all of our desires while solving our problems. The aesthetic of the installation also sits somewhere between the early Tim Burton set designs in films like Beetlejuice (1989) and the imaginary, charming creatures of nonsensical proportions that populate the pages of Dr. Seuss’ children’s books.

Bolink stands out among the growing group of artists who are making work with or about the technology of artificial intelligence, such as Ross Godwin and Sascha Pohflepp. It is more lyrical and subtle in its messaging, and the techniques that undergird it are rooted in classical arts training, like pencil drawing and kiln-fired sculpture. The premier of Bolink’s Oracle accompanies several other of his works at Club Solo in Breda, some of which are exhibited for the first time. They articulate a journey across media with a penchant for exploring recursiveness and a sustained curiosity for how technology alters our collective experience. The artists also approaches the interaction with the machines as an anthropologist might, seeking to understand a non-human entity with empathy and imagination, withholding judgment and exploring with wonder. He has said, “I feel there is an intelligence on the other side of the screen.”

The work Grand Piiiiiano Oracle, together with Bolink’s other projects that were co-created with digital platforms such as Pinterest and apps such as Goggles, allow us to behold that intelligence, but experience it mediated through the artist’s poetic gestures in materials, light, sound, and space. This invites us to question the nature of creativity, to contemplate whether it is confined to the human realm, in which case new technologies are akin to tools like the camera that gave rise to photography, or if we stand on the brink of a new era, in which creating becomes a truly shared experience, with a non-human entity. If indeed this is our new reality, Bolink is a pioneer of the new artistic terrain and we can expect Google’s answer to “what is art?” will be changing.

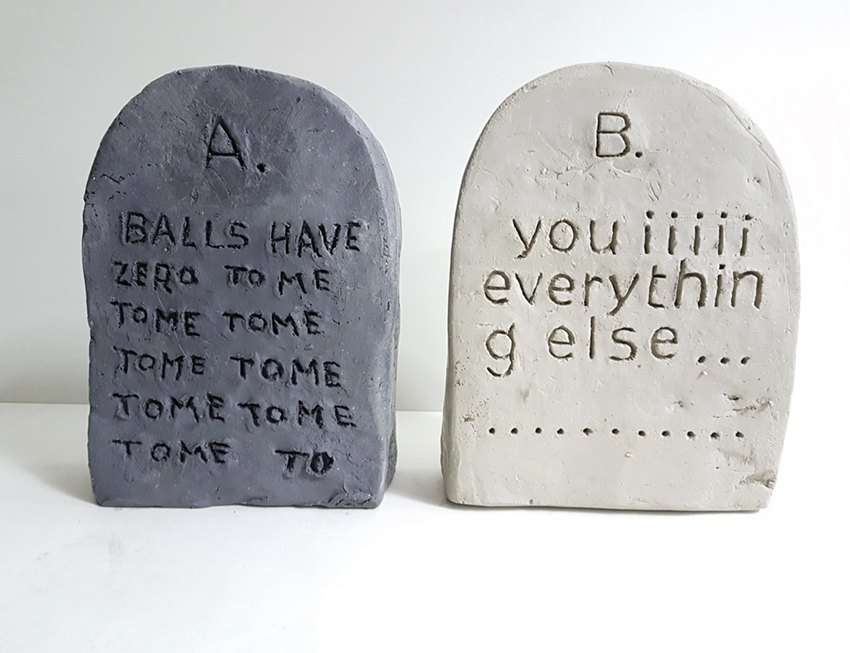

Alice and Bob

unglazed ceramics, 2018, 21 x 40 x 6 cm

Fragment of a dialogue between two computers learning to negociate at Facebook a.i. lab, carved in a massive block of clay. The fragment went viral when several sources stated that computers at Facebook were at the point of taking over control, forcing researchers to unplug them immediately. This was not the case at all, but the computers did start to develop a language of their own, making it impossible for the researchers to follow their strategies (which sometimes actually even lead to effective negotiations). See this paper for more scientific background.

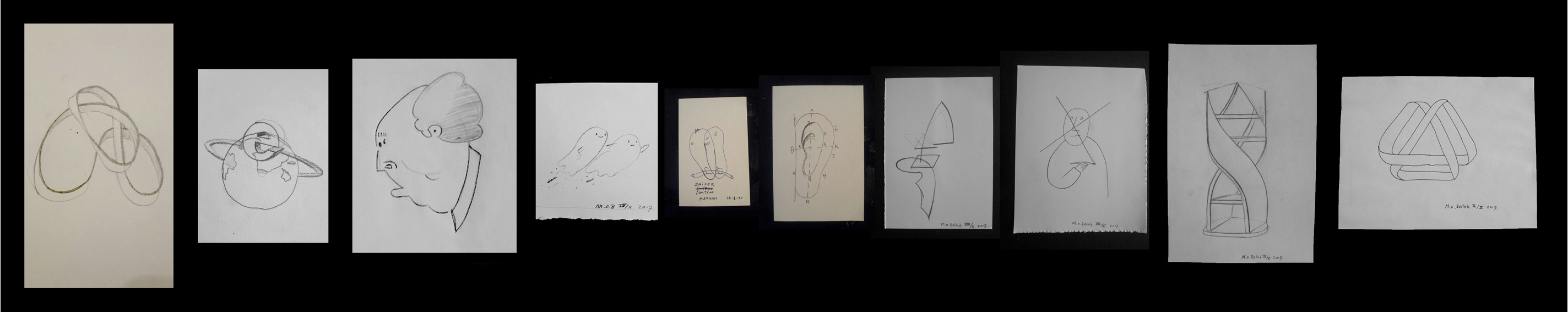

The Oracle, 10 drawings, first from the left created by the artist, all others hand-copied from Pinterest boards, 2017, 28 x 170 cm.

I Pick You, 2017, ceramics, 7 x 70 x 15 cm, co-created with My Garden App, originally developed for recognizing plants and flowers,

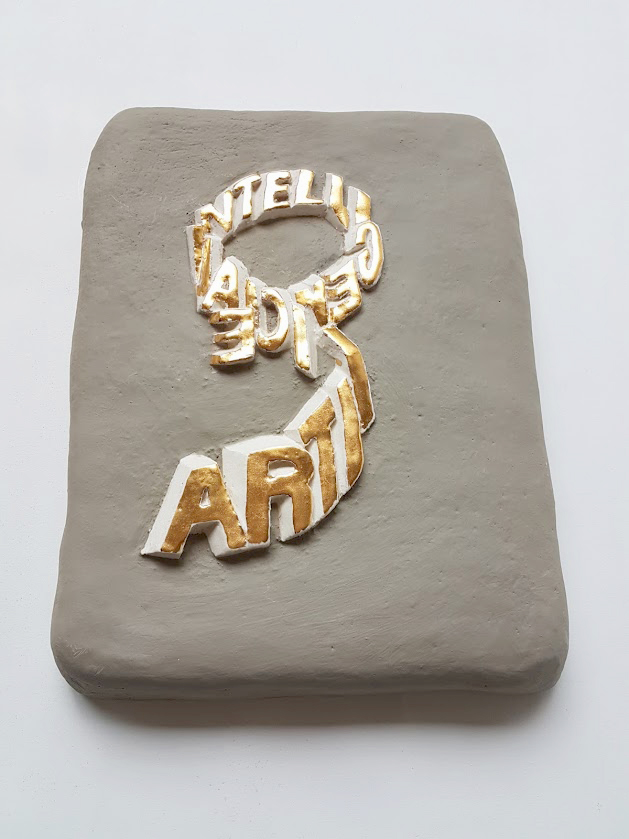

Artificial Intelligence, 2016, ceramics and gold, 6 x 20 x 28 cm,